The Squash Workflow

The first workflow we're going to talk about is the "squash workflow," the one

preferred by jj's creator, Martin. It's called "the squash workflow" because

it uses a command we haven't interacted with yet, jj squash. The second reason

that I'm talking about this workflow first is that it is the workflow that

should appeal to people who are big fans of git's index, and I think comparing

and contrasting the two is interesting.

The workflow goes like this:

- We describe the work we want to do.

- We create a new empty change on top of that one.

- As we produce work we want to put into our change, we use

jj squashto move changes from@into the change where we described what to do.

In some senses, this workflow is like using the git index, where we have our

list of current changes (in @), and we pull the ones we want into our commit

(like git add).

Starting work by describing it

Let's recap where we are in our project: @ currently is an empty commit:

> jj log

@ ywnkulko steve@steveklabnik.com 2024-02-28 20:40:00.000 -06:00 46b50ed7

│ (empty) (no description set)

◉ puomrwxl steve@steveklabnik.com 2024-02-28 20:38:13.000 -06:00 7a096b8a

│ it's important to comment our code

◉ yyrsmnoo steve@steveklabnik.com 2024-02-28 20:24:56.000 -06:00 ac691d85

│ hello world

◉ zzzzzzzz root() 00000000

Let's describe the work that we want to do:

$ jj describe -m "print goodbye as well as hello"

Working copy now at: ywnkulko 4bfe3940 (empty) print goodbye as well as hello

Parent commit : puomrwxl 7a096b8a it's important to comment our code

This change is currently empty, but we've now given it a useful name. This is the change we're going to build up over time. But for now, it's empty.

Create a new empty change

We need a place to hold our changes until we decide if we want to put them in our commit or not. So let's make a new one:

$ jj new

Working copy now at: rkvxolny 5e020e00 (empty) (no description set)

Parent commit : ywnkulko 4bfe3940 (empty) print goodbye as well as hello

We now have our change. It's also empty! There's no issue having two empty commits, one after the other. And since we are using this like an index, we don't really need to give it a name either. It's just a scratch space, but since it's part of a change, we're "always committed" in a sense.

Now it's time for the fun stuff.

Use jj squash to move things into our "real" change

Let's make a change to our code:

/// A "Hello, world!" program. fn main() { println!("Hello, world!"); println!("Goodbye, world!"); }

Now that our "feature" has been implemented, let's see our current changes:

$ jj st

Working copy changes:

M src\main.rs

Working copy : rkvxolny aee5266d (no description set)

Parent commit: ywnkulko 4bfe3940 (empty) print goodbye as well as hello

We now have an even wilder situation than before: our current change has stuff

in it, but the parent is empty! Let's change that. We want to take our change

from our "staging area" and put it into our commit (change). We can do that with

jj squash:

$ jj squash

Working copy now at: oopolqyp 9fb63b14 (empty) (no description set)

Parent commit : ywnkulko ed71bb54 print goodbye as well as hello

Lots of changes here! @ is now empty, with no description, and the parent is

now no longer empty. Our changes are now in ywnkulko.

What we did is kind of the equivalent of git commit -a --amend. But what about more

focused changes? Well, if we only want to add a specific file, like git add <file> && git commit --amend we can pass it as an argument. Because we only had

one file, the previous command was equivalent to

$ jj squash src/main.rs

But we can also get the equivalent of git add -p && git commit --amend, where

we only add parts of a file to our commit. And it's gonna blow your mind.

Make a few changes around your source file, and then do this:

$ jj squash -i

This will bring up a TUI!

By default, it's showing a file-level view: we have our one file, and the ( ) indicates that

we haven't selected to include this. We could do so by hitting space, and that

will fill the parenthesis in with a ● (screenshot outdated and shows an x):

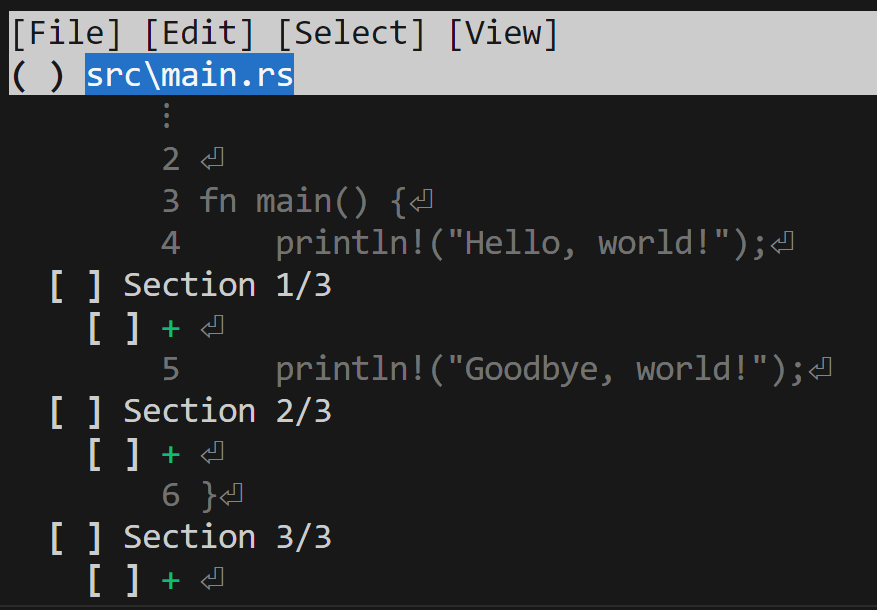

Let's press space again to undo that, and then hit f to toggle "folding":

I added empty spaces in a few places, and you can see each individual section and line has its own checkbox. We can use the mouse to click, or arrow keys to navigate, and space to toggle if we're accepting these changes.

Once we're done, we can hit c to confirm our changes. I'm not selecting any,

since these were just nonsense stuff I wanted to add to show off the TUI. I

don't want to keep them at all, so let's just dump them. We can get rid of

the stuff in @ with jj abandon:

$ jj abandon

Abandoned commit oopolqyp 44665581 (no description set)

Working copy now at: ootnlvpt 97b7a559 (empty) (no description set)

Parent commit : ywnkulko ed71bb54 print goodbye as well as hello

Added 0 files, modified 1 files, removed 0 files

We've thrown away oopolqyp, and jj has helpfully made a new empty change

for us.

This is the kind of stuff I mean when I say "the same power, but less concepts." We've got the tools that the index gave us, but they're simpler because we don't use some of them on the index, and some on commits: we use them all on commits.

That also implies that "the same power" isn't exactly true: jj squash is

more powerful than git add because it can work on any change and its parent,

moving stuff between them. This gets into the kind of shenanigans you can get

up to with git rebase -i, without the need for another command like that.

Simpler, but more powerful, thanks to orthogonality.

Recap and thoughts

This workflow is not super different than our previous one, but by adding one

more command, we get a bit more power. And we've learned that we can use

jj squash to move contents of changes into their parent.